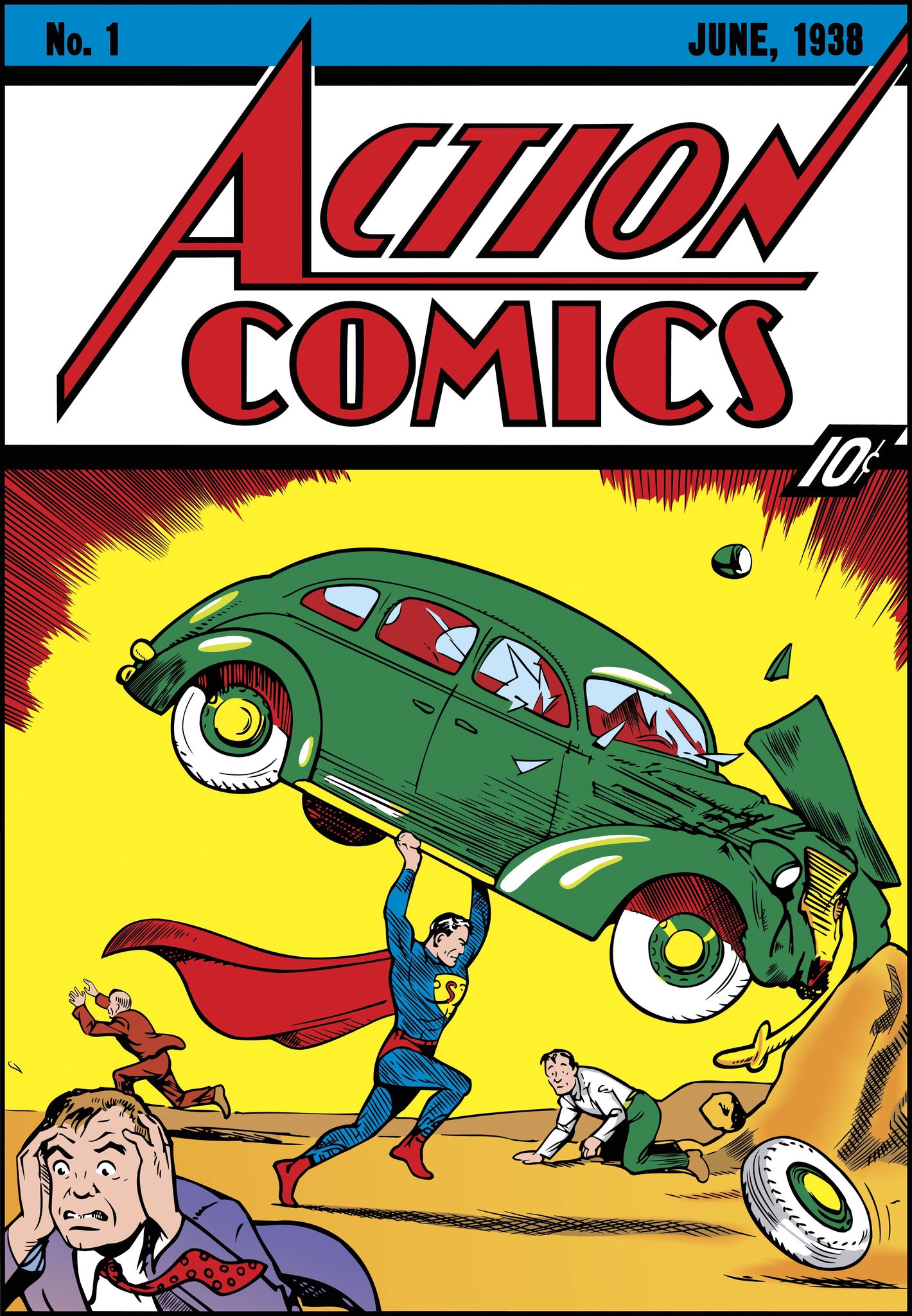

I love Superman. From my vantage point, Superman’s superiority is not even up for debate. He is the greatest superhero ever created. I know: it’s not trendy to say that. Batman is cooler. I guess you are allowed to hold your (incorrect) opinion.

I read a thought-provoking article entitled, “Let Superheroes Die.” Its basic premise is that too many people tasked with telling superhero stories these days take too much advantage of the well-worn story arc that involves the death and resurrection of the superhero. In particular, these storytellers do not make the death of the superhero real enough — within a matter of minutes, the death is resolved with resurrection. Instead, these storytellers should consider allowing the superhero actually to die permanently, or at least long enough to be real and painful. To quote the article:

Audiences don’t see a dead superhero and think, “My word, what a significant and final consequence of this plot line! I am the picture of shock!”

They think, “Huh. I wonder how they’re going to walk this back before the end of the movie.”

Watching this play out is sort of like watching a magician at a kids’ birthday party: the kid might genuinely be in shock, but the adults know that the whole act is an illusion, even if they don’t understand how. They simply wait around for the “reveal.”

The DC Universe aptly achieved something more, arguably, when they killed Superman and then waited a year to bring him back. Sure, he came back, but they gave it long enough for the characters and the readers to move out of denial and into acceptance and contemplation — what will the world be like now that Superman is really gone?

Grief is a funny thing. It is so essential to humanness, yet we ignore its existence, downplay it, or find all sorts of hoops to jump through in order to redefine it. We squirm when we encounter someone who has experienced real loss. We tell them that everything will be O.K. We try to make them laugh. Anything but allowing them, and even ourselves, to embrace the gravity of loss and death.

I so badly want always to believe that everything works out happily in the end. And perhaps it does in some sort of eschatological sense. But I’m convinced that even in that case, loss is real and painful, and any sort of healing that might come after it will involve deep embrace of grief by those who have lost, and intimate sharing of that grief by others. Because let’s face it: when someone dies, they aren’t really “gone.” Instead, they are as present as ever, yet they stand by silently and deafly, unable to speak and to hear, unable to see and be seen. Why loss hurts is precisely because that person isn’t gone from our minds.

One of the main reasons that the author of this article suggests for allowing a superhero to stay dead is that it gives everyone a chance to reflect on the essence of that character. What is life like without them? What hole is left? I would say the same thinking applies to any death. By allowing others a space to embrace the loss, and even by sharing in it with them, perhaps we give space for the silence to become painfully tangible, for the hole left by that person to be observed.

My own experience has led me to believe that one of the holiest spaces is standing with someone who grieves. No words will do; only one’s presence can even begin to do anything.

“Why loss hurts is precisely because that person isn’t gone from our minds.”

Wow, I have never thought of it like that…I love it when new perspectives are shared and it stops me in my tracks!

Awesome! Means a lot to me that you’re reading, Lindsey!